|

Press Releases

"SCIENCE interview with Shaul Mukamel," (December 10, 2021)

"QnAs with Shaul Mukamel," (July 2, 2018)

"ECNU NEWS CENTER," (February, 2018)

"UChicago News," (May, 2017)

"NSF highlights," (June, 2016)

"Chemical & Engineering News," (October, 2015)

"National Academy of Sciences," (April, 2015)

"ACS National Awards," (September 24, 2014)

"Hamburg Prize Award, 2012," (November 7, 2012)

"Light-harvesting molecule takes shape," Currents (July 24, 2000)

"Bigger Isn't Always Better for Molecular Light Funnels," Photonics Spectra (November, 2000)

"Scientists Construct Model to Illustrate Behavior of Optically Excited Materials," Photonics Spectra (October, 1997)

"A New Dimension in Spectroscopy," Chemical & Engineering News (February, 2000)

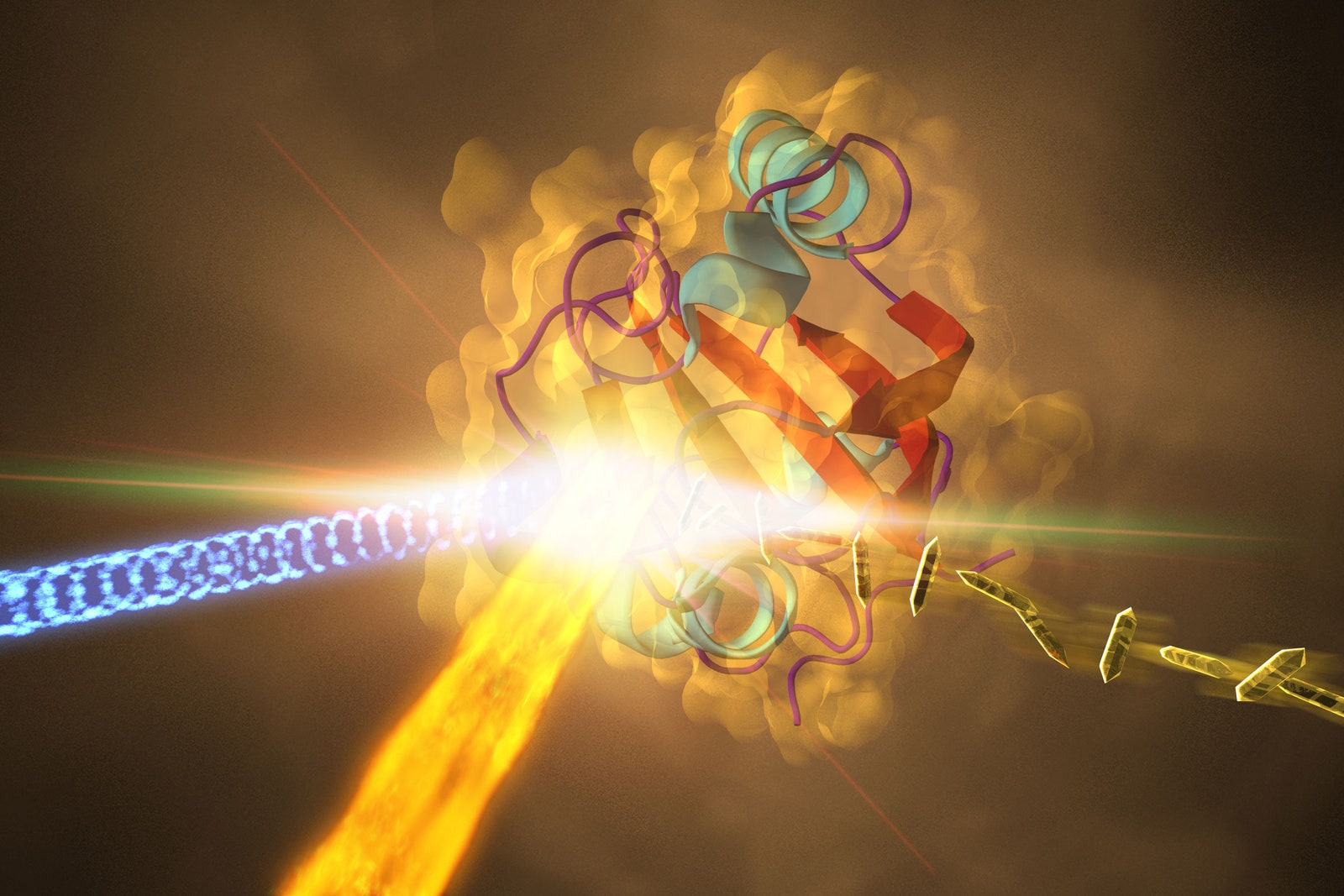

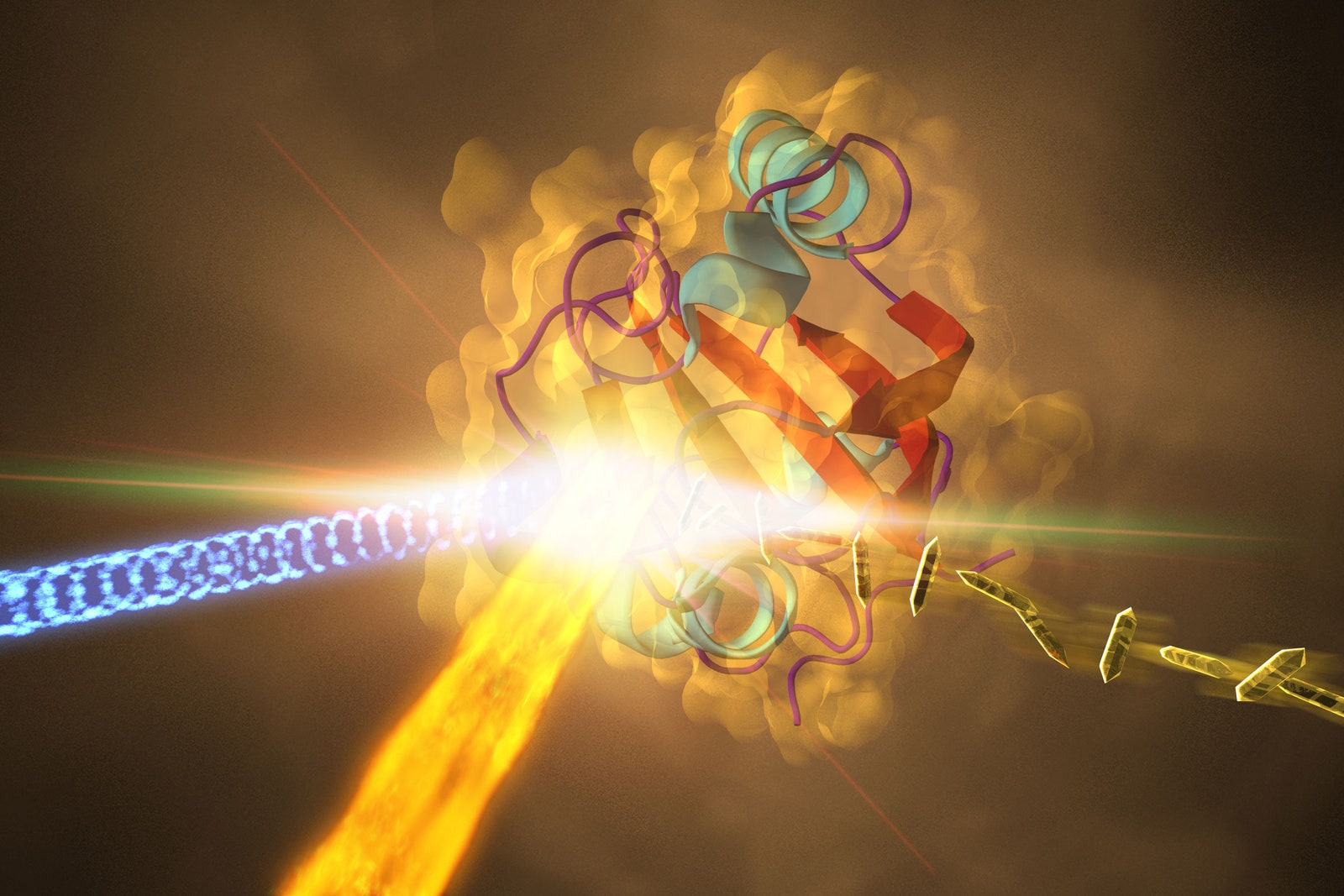

To See Proteins Change in Quadrillionths of a Second, Use AI

Researchers have long wanted to capture how protein structures contort in response to light.

But getting a clear image was impossible—until now.

|

|

HAVE YOU EVER had an otherwise perfect photo ruined by someone who moved too quickly and caused a blur? Scientists have the same issue while recording images of

proteins that change their structure in response to light. This process is common in nature, so for years researchers have tried to capture its details. But they

have long been thwarted by how incredibly fast it happens.

Now a team of researchers from the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee and the Center for Free-Electron Laser Science at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron in Germany have combined machine learning and quantum mechanical calculations to get the most precise record yet of structural changes in a photoactive yellow protein (PYP) that has been excited by light. Their study, published in Nature in November, showed that they were able to make movies of processes that occur in quadrillionths of a second.

When PYP absorbs light, it absorbs its energy, then rearranges itself. Because the protein’s function inside the cell is determined by its structure, whenever PYP folds or bends after being illuminated, this triggers huge changes. One important example of proteins interacting with light is in plants during photosynthesis, says Abbas Ourmazd, a physicist at UWM and coauthor on the study. More specifically, PYP is similar to proteins in our eyes that help us see at night, when a protein called retinal changes shape, activating some of our photoreceptor cells, explains Petra Fromme, director of the Biodesign Center for Applied Structural Discovery at Arizona State University, who was not involved with the study. PYP’s shape change also helps some bacteria detect blue light that may be damaging to their DNA so they can move away from it, Fromme notes.

Details of this important light-induced molecular shape-shifting, called isomerization, have eluded scientists for years. “When you look at any textbook, it always says that this isomerization is instant upon light excitation,” says Fromme. But, for scientists, “an instant” is not unquantifiable—the changes in the protein’s structure happen in the remarkably short amount of time known as a femtosecond, or a quadrillonth of a second. A second is to a femtosecond what 32 million years is to a second, Fromme says.

Scientists experimentally probe these incredibly short timescales with similarly short flashes of x-rays. The new study used data obtained in this way by a team led by UWM physicist Marius Schmidt at a special facility at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Here, the researchers first illuminated PYP with light. Then they hit it with an ultrashort x-ray burst. The x-rays that bounced off of the protein—called diffracted x-rays—reflected its most recent structure in the same way that light reflected from objects helps make conventional photographs. The briefness of the pulses allowed scientists to get something like a snapshot of the positions of all of the protein’s atoms as they moved, similar to the way a camera with a very fast shutter can capture the different positions of a cheetah’s legs as it runs.

But even the shortest x-ray flashes have typically not made for a fast enough “shutter” to get a femtosecond-by-femtosecond record of a protein’s shape change. "A major problem in analyzing diffraction signals is that the x-ray source is noisy,” says Shaul Mukamel, a chemist at the University of California, Irvine who was not part of the study. In other words, the x-ray flash always leads to at least some blurriness. Imagine the protein as a contortionist folding itself into a pretzel. Using x-rays, scientists can get a clear image of its relaxed pose immediately after it absorbs the light energy that spurs the contortion, and of its intertwined limbs at the end. But any images of its in-between motions would be fuzzy.

However, Mukamel adds, x-ray experiments like the one analyzed in the new study tend to collect huge datasets. Chemists like himself are always trying to innovate ways to unearth new information from them, he says. In the new study, using artificial intelligence to analyze the data was key.

Ourmazd’s Wisconsin team, led by research scientist Ahmad Hosseinizadeh, used a machine learning algorithm to extract unprecedentedly precise information from the experimental x-ray diffraction data. Ourmazd compares their method to an innovation in taking a three-dimensional scan of a person’s head. “Normally, what happens if you want a 3D image of somebody's head, you sit them down, get them to be still, and take lots of pictures,” he says. But his group’s algorithm does something more like taking a series of photos from different angles and at different times as the person repeats the same motion, like slightly turning their head. Then the AI extracts the complete 3D image from this group of snapshots and learns what the entire movement should look like, creating a sort of animated “movie” of it. “Using artificial intelligence at each time point, we’d reconstruct a three-dimensional picture of the head. We’d have a 3D movie as a function of time,” Ourmazd says.

In the PYP experiment, the machine learning algorithm was given data from multiple nearly-identical proteins that had been imaged in sequence. (Researchers couldn’t reuse the same protein, because they get damaged by the x-ray.) The AI extracted the details of the process without the blurriness of the x-ray flashes, and it uncovered what the blur had been obscuring. Remarkably, these images showed how electrons inside the protein move within frames that are only femtoseconds apart. These movies—which the team later slowed down enough to allow the human eye to track the change—show electrons moving from one part of the protein to another. Their motion inside the molecule indicates how the whole thing is changing its structure. “If my thumb moves, then the electrons inside of it have to move with it,” Ourmazd offers as a comparison. “When I look at the change in the charge distribution [of the thumb], it tells me where my thumb was before and where it has gone.”

The protein’s reaction to light has never been observed in such small time increments before. “There's a lot more information in datasets than people generally think,” Ourmazd says.

To better understand the motions of electrons, the Wisconsin team worked with physicists at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron who performed theoretical simulations of the protein’s reaction to light. The electrons and atoms within the protein have to move according to the laws of quantum mechanics, which act as something like a rulebook. Comparing their results to a simulation based on those rules helped the team understand which of the allowed moves the protein was performing. This brought them closer to understanding why they saw the motions they did.

The union of quantum theory and AI encapsulated in the new work holds promise for future research into light-sensitive molecules, says Fromme. She emphasizes that a machine learning approach can extract lots of detailed information from seemingly limited experimental data, which may mean that future experiments could consist of fewer long days doing the same thing over and over in the lab. Mukamel agrees: "This is a most welcome development that offers a new path for the analysis of ultrafast diffraction measurements."

Coauthor Robin Santra, a physicist at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron and the University of Hamburg, believes that the team’s novel approach could change scientists’ thinking about incorporating data analysis into their work. “The combination of modern experimental techniques with ideas from theoretical physics and mathematics is a promising route towards further progress. Sometimes, this may require scientists to leave their comfort zone,” he says.

But some chemists would like to see the new approach examined in even more detail. Massimo Olivucci, a chemist at Bowling Green State University, points out that PYP’s response to light includes something like a singularity in its energy spectrum—a point where the mathematical equations for calculating the protein’s energy “break.” This kind of occurrence is as important to a quantum chemist as a black hole is to an astrophysicist, because it is another instance in which the laws of physics, as we understand them today, fail to tell us exactly what is happening.

According to Olivucci, many fundamental processes in chemistry and molecular physics involve these “rule-breaking” features. So understanding the minute details of what a molecule is doing when laws of physics can’t offer clarity is really important to scientists. Olivucci hopes that future work with the machine learning algorithm from the new study will compare its “movies” to theoretical simulations that contain atomistic detail—rulebooks specifying what every single atom in the protein can and cannot do. This could help chemists determine the fundamental reasons why some of the smallest parts of PYP perform some of its fastest moves.

Ourmazd also notes that his team’s approach could help uncover even more about PYP’s response to light. He would like to use the algorithm to observe what happens slightly before the protein absorbs light, before it “knows” that it is about to start contorting, rather than immediately after the absorption, when it is locked into the motion. Additionally, he notes, instead of using flashes of x-rays, scientists could throw ultrafast electrons at the protein, then record their bouncing off to produce even more fine-grained snapshots that the AI could analyze to achieve an even more detailed animation of the process.

Ourmazd would also like to tackle astrophysics and astronomy next, two fields in which scientists have long been taking images of a changing universe, and from which an AI might extract useful data—although he doesn’t have a specific experiment in mind yet. “The world's our oyster, to some extent,” he says. “The question is: What are the most important questions to ask and realistically expect to answer?” |

Interview by KARMELA PADAVIC-CALLAGHAN, Science Dec 10, 2021

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

UCI’s Shaul Mukamel was interviewed by science writer Farooq Ahmed for PNAS to expand on the theoretical research performed here on campus by the Mukamel laboratory.

|

|

A New Method of Multidimensional Spectroscopy Based on Single Photon Counting and Coherence Measurement

UCI’s Shaul Mukamel and former postdoc and Visiting Professor Konstantin Dorfman are being recognized

“for developing a new method of multidimensional spectroscopy based on single photon counting and coherence measurement"

|

|

Board of Directors of The Optical Society (OSA) has selected Shaul Mukamel as the 2017 recipient of the William F. Meggers Award

UCI’s Shaul Mukamel is being recognized

“for developing the theoretical framework of coherent multidimensional spectroscopy for electronic excitations in the optical regime and proposing extensions to the x-ray spectral regime"

|

.jpg)

|

University to bestow three honorary degrees at Convocation

|

|

"Shaul Mukamel- recipient of an honorary degree of doctor of science from the University of Chicago"

"Shaul Mukamel- honorary degree of doctor of science video at the University of Chicago"

|

Spectroscopic Observation of Ultrafast Light Induced Processes in Molecules – Chasing Schrödinger’s Cat

|

|

"Mukamel NSF Highlights"

|

You are in the news "Celebrating the International Year of Light"

|

|

"Celebrating the International Year of Light"

|

UCI’s Shaul Mukamel elected to National Academy of Sciences

Chemistry researcher receives top honor for work with ultrafast laser light

|

|

|

Irvine, Calif., April 29, 2015 – Shaul Mukamel, a UC Irvine Distinguished Professor of chemistry who probes molecular secrets using ultrafast pulses of laser light, has been elected to the National Academy of Sciences.

Mukamel, 67, joins 84 new members and 21 foreign associates announced April 28 by the academy, a distinction considered one of the highest honors in science.

“It’s very nice to be recognized by the community,” Mukamel said. “I feel that the environment of support at UCI has contributed a lot to my work and to my success, and I am grateful to have this honor.”

Mukamel has been hugely influential in his field, said UCI physical sciences dean Ken Janda.

“Professor Mukamel’s work has influenced my own for almost 40 years,” he said. “He explains complex theories clearly and concisely to help experimentalists know which data will make an impact. This is one of many reasons he has had such an important impact. We are lucky to have him at UC Irvine.”

Chancellor Howard Gillman said Mukamel is a trailblazer.

“This extraordinary recognition only confirms what we have long known: Shaul Mukamel is a true pioneer whose insightful and profound research has transformed his field and created important new areas of exploration,” Gillman said.

“Since our founding 50 years ago, UCI scientists have been at the forefront of scientific advancement, and Shaul joins 40 other current UCI faculty members who have been welcomed into one of the National Academies. We couldn’t be happier for him and more proud of him.”

Mukamel is well known in the research community for designing cutting-edge experiments to reveal how molecules interact with short laser pulses. His theoretical work in the realm of “ultrafast nonlinear spectroscopy” seeks to understand and control chemical reactions via lasers.

His recent investigations include employing the X-ray regime of the light spectrum and the quantum properties of light to observe the motion of electrons and atomic nuclei in real time.

“I was always interested in using lasers to study molecules,” Mukamel said. “I have been keeping track of the state-of-the-art new technologies and anticipating what will come and trying to design experiments that will make use of these advancements. My driving force is exploring the fundamental science.”

But while his work could open new doors of basic understanding, it also has deep implications for practical applications in biomedical imaging and materials science, including better methods for harvesting solar energy.

Mukamel’s 1995 book Principles of Nonlinear Optical Spectroscopy is widely relied upon in this research field.

The National Academy of Sciences has a total of 2,250 active members, including 25 from UC Irvine; nine of those are in UCI’s School of Physical Sciences. |

|

|

|

|

The list of scientists to be honored by the American Chemical Society (ACS) in 2015 contains many prominent names. Professor Jacqueline K. Barton of the California Institute of Technology will receive next year's Priestley Medal for her work on electron transport in DNA, her dedication to training young investigators, and her unwavering support for the chemistry enterprise. The Priestley Medal is the highest distinction conferred by the ACS. "I am extremely honored and grateful to receive the Priestley Medal, but it is really a prize for all my students and coworkers, who have worked with courage and tenacity to unravel new things about the chemistry of DNA," Barton says. DNA-mediated charge-transport (DNA CT) chemistry provides a sensitive means to detect DNA damage/mistakes and monitor protein binding and protein reactions on DNA. "We are exploring how this chemistry may be utilized within the cell for long-range signaling as a first step in finding DNA lesions to repair." The Barton group is currently interested in synthesizing and characterizing DNA-binding probes, examining the biological implications of DNA CT, and designing electrochemical devices that can be used to sense DNA damage or report on DNA and protein binding events.

"Jackie Barton is an outstanding choice to be the 2015 Priestley Medalist," said ACS executive director and chief executive officer Madeleine Jacobs in an interview with Chemical and Engineering News. "She combines path-breaking research with service to the chemical profession in many arenas. She has also been a superb role model, not just for young women but for all young scientists, in her ability to balance her professional and personal life."

Jacqueline Barton received her BA from Barnard College and earned her PhD in Inorganic Chemistry at Columbia University. She has received many awards and recognitions including the National Medal of Science (2011), the ACS Gibbs Medal (2006), and the Weizmann Women and Science Award (1998).

The 2015 Ahmed Zewail Award in Ultrafast Science and Technology goes to Professor Shaul Mukamel of the University of California at Irvine for his theoretical studies on ultrafast dynamics and relaxation processes. "I am deeply honored by this award, and I am grateful to the ACS for this wonderful recognition," Mukamel says. "I am also thankful to the many talented students, postdocs, and collaborators who have made this award possible." The prize is named after the Chemistry Nobel Laureate Ahmed Zewail, who is considered a pioneer in the field of femtochemistry. "Receiving this award means a lot to me, since I have known Ahmed Zewail for over 35 years, starting in the early days of infrared laser chemistry," Mukamel says. "His tremendous contributions to chemistry, physics, and ultrafast science have always been a source of inspiration and were instrumental to my own research, which focused on connecting coherent optical signals with the underlying electronic and nuclear motions." Mukamel's proposal to employ sequences of ultrafast laser pulses to study electronic and vibrational dynamics in complex molecules helped create the rapidly developing field of coherent ultrafast multidimensional optical spectroscopy.

"This award is a long overdue recognition because Prof. Mukamel's contributions have been crucial to ultrafast science," says Professor Majed Chergui, an expert in ultrafast spectroscopy working at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in Switzerland. "Already over 25 years ago, he blended different types of spectroscopies into a common language. He then developed the concepts for interpreting and analyzing ultrafast results from different types of linear and nonlinear ultrafast methods." According to Chergui, this led to the proper theoretical framework required to interpret the new techniques. Since then, Mukamel and his colleagues have been refining and extending the application of the spectroscopic methods to shorter wavelengths, including the X-ray domain. "In these respects, he has been ahead of experimentalists and has guided them into novel areas of study, which deliver new insight into the ultrafast dynamics of complex systems," Chergui says. Some of the areas that have benefited from Mukamel's work include studies on protein folding and aggregation and investigations on photosynthesis and DNA damage and repair.

Shaul Mukamel obtained his PhD at the University of Tel-Aviv and has received several prizes including the 2003 Lippincott Award of the Optical Society of America, the 2011 Earle K. Plyler Prize for Molecular Spectroscopy of the American Physical Society, and the 2012 Hamburg Prize for Theoretical Physics.

Professor Ben L. Feringa (University of Groningen, the Netherlands) will receive one of next year's Arthur C. Cope Scholar Awards. He will be honored for his work in the fields of organic synthesis and supramolecular chemistry. Feringa has made important contributions to the study of molecular switches and motors and the development of asymmetric catalysis and stereoselective synthesis methods. According to W.R. (Wesley) Browne, a Professor at the University of Groningen and one of Feringa's former postdocs, in addition to all these achievements, the Dutch scientist has also inspired several generations of students and postdocs to take on seemingly impossible challenges in organic synthesis, catalysis, and their application in tackling real problems beyond organic chemistry. "I had the pleasure to work with Ben both as a postdoc and then as a colleague over the last 11 years," Browne says. "I remember that he told me that the lab is our playground for chemistry, and that we should do new exciting things even if -and in fact because- we have no idea if they will work or not! This was an understatement and over the years I am amazed how many successes have come from spur-of-the-moment ideas in discussions at a chalk board!"

Ben Feringa obtained his PhD at the University of Groningen. His research has been recognized with a number of awards including the Koerber European Science Award (2003), the Chirality Medal (2009), and the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) Organic Stereochemistry Award (2011). He graduated his 100th PhD student last December.

The 2015 ACS National Award recipients will be honored at an awards ceremony in March, in conjunction with the 249th ACS national meeting in Denver. The Arthur C. Cope Scholar Award recipients will be honored during the fall national meeting in Boston. Other awardees include Paul S. Weiss (California NanoSystems Institute), who will receive the ACS Award in Colloid and Surface Chemistry, Mark S. Gordon (Iowa State University), who will be honored with the ACS Award in Theoretical Chemistry, and Xiaoliang Sunney Xie (Harvard University), who will be distinguished with the Peter Debye Award in Physical Chemistry.

Photos: Left: Jacqueline Barton (California Institute of Technology) is next year's Priestley Medalist. Right: Shaul Mukamel (University of California at Irvine) will receive the 2015 Ahmed Zewail Award in Ultrafast Science and Technology.

|

Hamburger Preis für theoretische Physik awarded to Shaul Mukamel

|

|

|

The third international symposium "Frontiers in Quantum Photon Science" organised by the state excellence initiative (LEXI) culminated in the prize ceremony of the "Hamburger Preis für theoretische Physik" (Hamburg prize for theoretical physics). This year, the prize was awarded to Prof. Shaul Mukamel of University of California, Irvine.

The research awared, endowed with a personal prize money of 40.000 Euro and combined with a research stay at the University of Hamburg, was handed over by the senator for science and research of the federal state of Hamburg, Dr. Dorothee Stapelfeldt on November 07, 2012.

Shaul Mukamel, pioneer in the fields of nonlinear optics and multi-dimensional spectroscopy, is one of the most important theoretical physicists wordwide. He is awarded for his outstanding contributions to physics in the last decades.

In 2012, the prize was awarded for the third time, making Prof. Mukamel the third laureate after Macej Lewenstein and Peter Zoller. The prize is one of the highest-valued research awards and has received very high attention in the scientific community world wide. It is combined with a guest stay for teaching and research at the university of Hamburg.

|

|

|

Prof. Dr. Dieter Lenzen, president of the universtiy of Hamburg, Dr. Dorothee Stapelfeldt, Senator for Science and Research of the federal state of Hamburg and Petra Herz, chairwoman of the Joachim Herz foundation with the laureate Shaul Mukamel (from left to right). Photo: Alexander Grote

|

The following appeared in the July 24, 2000 Issue of the University of Rochester's Currents:

Light-harvesting molecule takes shape

For 20 years, researchers have experimented with artificially created, tree-like molecules that act like antennae and might someday play a key role in a number of processes, from releasing a drug inside the body to converting light to energy more efficiently than Mother Nature. Now researchers at the Unversity have computed what seems to be the most efficient configuration for one class of these molecules, and have published their results in the July 10 issue of Physical Review Letters.

"These are giant, light-harvesting molecules," explained Shaul Mukamel, professor of chemistry. "Each one is designed like a net that captures light and funnels its energy into its core, where we can make it do almost anything we want."

The fractal-shaped molecules, called "dendrimers," are currently used in laboratories to control chemical reactions, since researchers can use them to release a chemical at the perfect moment, but only recently have scientists realized some of their potential. The organic molecules look like snowflakes, with tiny limbs branching out in all directions to capture a ray of light and channel its energy into the molecule's heart. There the light energy can be harnessed to generate power like a super-efficient photoelectric cell or to release a chemotherapeutic drug inside a tumor after it's been carried through the bloodstream. Dendrimers might even one day act as the initial necessary step in photosynthesis, improving the light-harvesting task performed naturally within any green leaf, to yield crops that can grow where none grew before.

To determine the most efficient configuration, graduate student Subhadip Raychaudhuri and chemistry research associate Vladimir Chernyak worked with Mukamel and Yonathan Shapir, professor of physics, to run thousands of computer simulations. These simulations incorporated everything known about the way atoms interact in order to see whether there was a certain shape or size of dendrimer that caught and funneled light's energy best. "What surprised us is that there is a point of diminishing returns," said Shapir.

Many scientists have envisioned building bigger and bigger molecules, since a dendrimer needs as many light-catching limbs as possible to capture light, much as a big tree snares more light than a smaller one. But the researchers found a problem: the larger the molecule, the harder time it had funneling that light energy toward its center.

In research funded by the National Science Foundation, the team of chemists and theoretical physicists ran the simulations until they found the magic number for one particular family of dendrimers: nine. The dendrimers could branch out up to nine times before their ability to funnel light became compromised. The team expects the findings to set the guidelines for the synthesis of large fractal-like dendrimers that could be used in many chemical reactions, from making magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans more accurate, to converting sunlight to energy for weakened plants.

The following appeared in: Photonics Spectra (November 2000, Pg. 32) - By Kevin Robinson The following appeared in: Photonics Spectra (November 2000, Pg. 32) - By Kevin Robinson

Bigger Isn't Always Better for Molecular Light Funnels

ROCHESTER, N.Y. - Researchers at the Unversity of Rochester have determined the ideal size for a light-harvesting molecule that one day may improve the light gathering of everything from photoelectric cells to genetically engineered plants. Led by physics professor Ynothan Shapir and chemistry professor Shaul Mukamel, the team has learned that after a certain size, the molecule phenyacetylene begins to lose its efficiency at channeling light to its center.

Over the past decade, scientists have experimented with artificial molecules that funnel light. Until recently, many thought that the larger the molecule, the more light it could collect. The researchers determined that this is not the case and have devised a method to determine the optimum size of such molecules.

To test how size affects efficiency, the researchers developed computer models to gauge how long it takes the energy of a photon to reach the core, where it causes a desired chemical reaction. "These calculations dealt with two particular aspects of the dendrimers: the nonlinear potential and the inherent randomness due to their interactions with the solvent," Mukamel said.

Useful for thermal sensors

Because dendrimers-molecules that display a fractal branching structure-have branches of different lengths, the excitation energy moves in a nonlinear fashion toward the center. In addition, excitations take random paths to the center and can get lost on the structure in the process.

The researchers first studied the effects separat5ely; then they combined them. "To include both the nonlinearity and the randomness, we had to run repeated computer simulations to mimic the many different ways the randomness can take," Shapir said. The found that if the molecule is too large, either effect increases the time for the excitations to reach the center. "Luckily, the optimal sizes associated with these two different effects were found to be identical," he said, so optimizing phenylacetylene's size for one factor will not adversely affect its performance by the other.

The researchers classified the molecule by the number of times it branched, which is known as its generation. According to Mukamel, their calculations show that for phenylacetylene the optimal size is nine generations.

Because the work is in its early stages, Mukamel, said, any applications are only possibilities. The model ahs potential in a variety of fields, tailoring dendrimers for use as drug delivery systems in medicine, as thermal sensors and in photovoltaics.

The research team published its findings in the July 10 issue of Physical Review Letters.

|

Scientists Construct Model to Illustrate Behavior of Optically Excited Materials

The following appeared in: Photonics Spectra (October 1997, Pg. 50) |

A group of researchers based at the University of Rochester and led by Shaul Mukamel has developed a set of theoretical models that illustrate how properties of both small and large molecules change when optically excited. Up until this point, scientists could conduct calculatiosn on the properties of single molecules but lacked a method to explain the behavior of large molecular structures. Mukamel said the new methods would enable scientists to better manipulate the structure of optical materials.

A group of researchers based at the University of Rochester and led by Shaul Mukamel has developed a set of theoretical models that illustrate how properties of both small and large molecules change when optically excited. Up until this point, scientists could conduct calculatiosn on the properties of single molecules but lacked a method to explain the behavior of large molecular structures. Mukamel said the new methods would enable scientists to better manipulate the structure of optical materials.

|

A New Dimension in Spectroscopy

Researchers hope that multidimensional IR and Raman techniques will complement the capabilities of multidimensional NMR

By Stu Borman

Chemical & Engineering News

February 7, 2000 (pp. 41-50)

|

.

|

| | | | | | |

.jpg)

A group of researchers based at the University of Rochester and led by Shaul Mukamel has developed a set of theoretical models that illustrate how properties of both small and large molecules change when optically excited. Up until this point, scientists could conduct calculatiosn on the properties of single molecules but lacked a method to explain the behavior of large molecular structures. Mukamel said the new methods would enable scientists to better manipulate the structure of optical materials.

A group of researchers based at the University of Rochester and led by Shaul Mukamel has developed a set of theoretical models that illustrate how properties of both small and large molecules change when optically excited. Up until this point, scientists could conduct calculatiosn on the properties of single molecules but lacked a method to explain the behavior of large molecular structures. Mukamel said the new methods would enable scientists to better manipulate the structure of optical materials.